Apollonian Order and Dionysian Chaos: The Dance of Solar-and-Earth Cult in Antiquity

The Ardhanarisvara, the androgynous union of Shiva and Shakti

The Promethean quest for spiritual ascendance takes place within the tension suspended between two poles of energy, represented by the masculine and the feminine. The masculine, or Apollonian principle, symbolizes the ascent towards rational knowledge, the concrete and visual, and the primacy of the word, or Logos. The feminine, or Dionysian principle, in contrast, represents the world of emotion, change and flux, and the descent into the subconscious (1). Mythologically, the tension and balance between these two poles has been represented in the various world mythologies: the defeat by the sun god Apollo of the serpent-beast Python, son of Gaia the Earth Mother, reflects the victory of order, reason, and law over the natural, instinctual, and animalistic energies of the Earth (2). Apollonian light shines victorious over the telluric and chthonic, relating “to the earth” and “to the underworld” respectively. This myth is repeated in various other traditions–the Babylonian, Egyptian, Vedic–and is also echoed in the monotheistic faiths. The association between temptation, sin, the woman and the snake–so prominent in the Book of Genesis–is counterbalanced by the establishment of God’s law, represented as the logos spermatikos, or “seminal word,” that brings into existence order and generates prosperity, growth, and ascendance towards the Good (3).

Eugene Delacroix-Apollo Slaying Python (c.1853) The Louvre

While it must be mentioned that historical subjugations of women were engendered in large part through myths and associations between woman and the chthonic powers of the underworld–the ability of women to generate life and their adherence to the clinical patterns of nature represented by the serpent (a symbol of immortality) and the moon–traditional societies have maintained balance between the ascendant and Promethean element of masculinity with the nurturing, instinctual, and protective aspect of the feminine. Witchcraft trials during the High Middle Ages notwithstanding, cultures from the Taoist in the Far East to Christianity have traditionally incorporated both the Apollonian and Dionysian in a kind of cosmic dance. In the Vedic tradition, the tandava dance between Shiva (Apollonian stillness and form) with Shakti (Dionysian energy, movement and chaos) results in a synthesis of Purusha and Prakriti (the masculine and feminine principles) in the divine form of Ardhanarishvara. This kind of balance between Yin and Yang can be seen replicated throughout other traditions. The ascendant Christ–bearer of the divine Logos–the Word of God–ascends skyward while his mortal self descends into the Earth. The masculine figure of God the Father is counterbalanced by the cult of Mary (herself a representative of deeper, chthonic elements in the European pagan tradition i.e. Mokosh, goddess of the Wet Mother Earth). Christ’s sacrifice is echoed in more ancient traditions. In the Mithraic Tauroctony of the ancient Romans, the sacrifice of the bull–a symbol of the telluric world of nature–releases life by inseminating the earth and providing the basis for divine order. The Greek logos spermatikos, that symbol of rational order and structure, is gently balanced by the kosmogonos, or, feminine instinct towards divine love, peace, and cosmic union (4). Finally, the grail legend itself–the sacred journey of Parcival and Galahad–is realized through the redemptive and idealized vision of a chaste maiden. allegorically representing the Virgin Mary, the Mother Church, as well as Sophia, the feminine face of God as divine wisdom and beauty, which carries the cosmic spark (5). Islamic interpretations, heavily influenced by Neo-Platonism and the realm of Perfect Forms, also maintained a sacred balance between ‘Aql (reason) and ‘Esk (divine love). The poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi most succinctly portrayed this sacred balance between the masculine and feminine:

“Reason is like a lantern on the road. Love is the road itself.”-Rumi

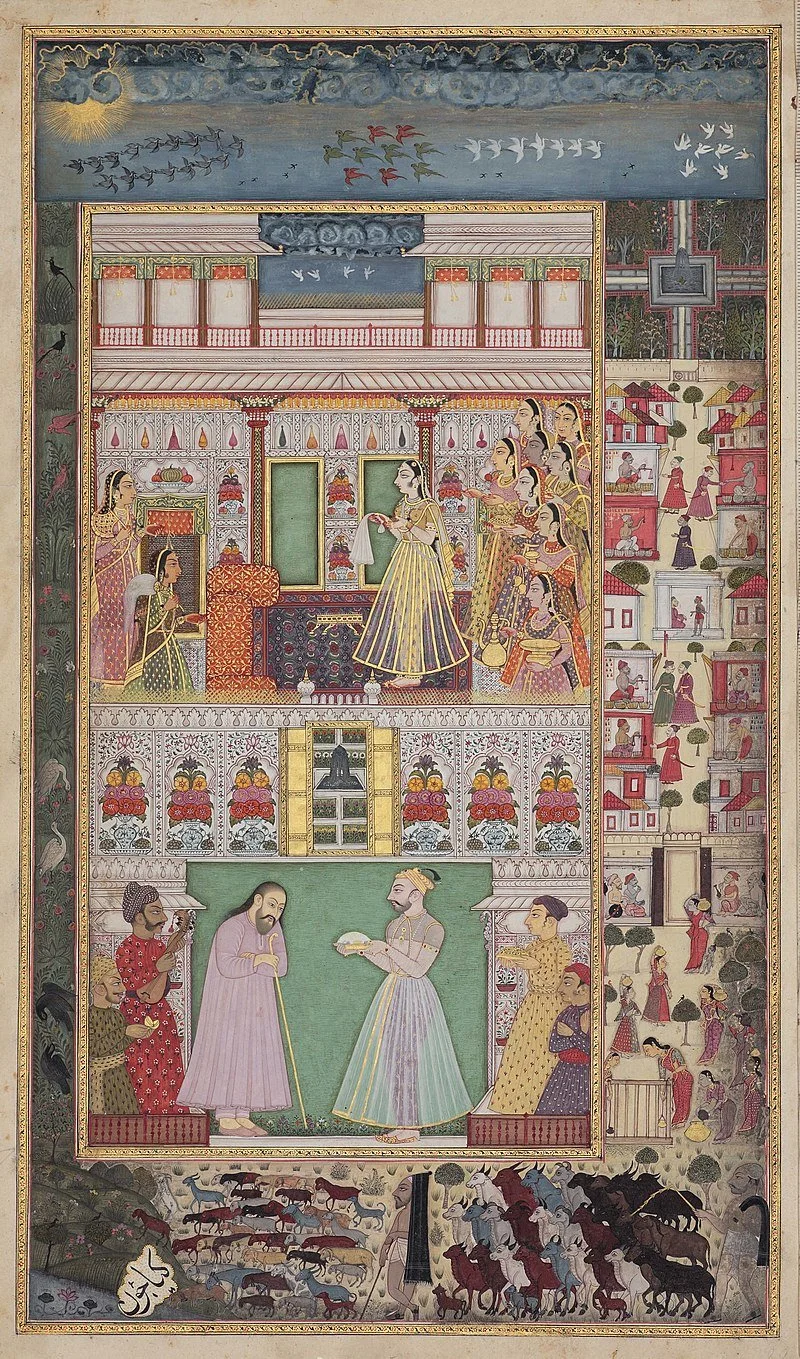

A scene from the Sufi mystic Nusrati’s Gulshan e-Ishq (The Rose Garden of Love) from a 1710 manuscript. In the upper panel, the queen resides, secluded in her private apartment, in Sophia-like wisdom (the divine feminine, or beloved held at a distance). In the lower panel, King Bikram, offers food to the holy man, Roshan e-Dil (meaning, “illumination of the heart.”), in a symbolic scene representing the union of ‘Aql (Reason) and ‘Esq (Divine Love).

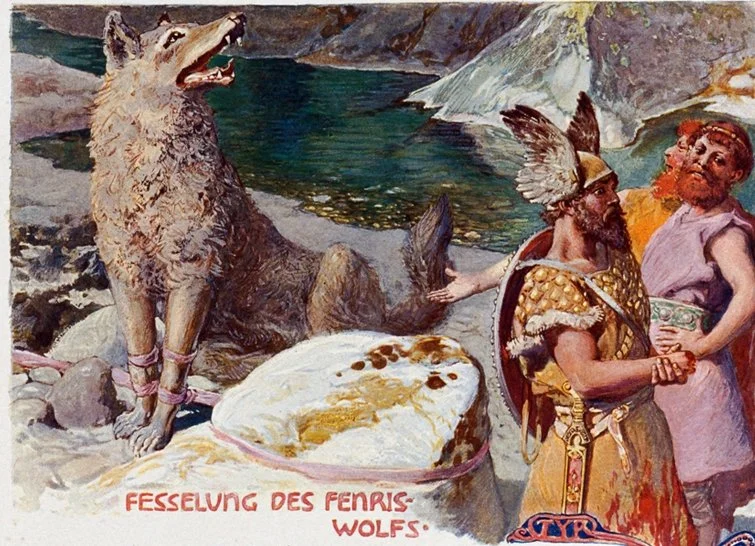

The tension between the masculine and feminine in mythology, and in particular, the establishment of Apollonian reason, order and transcendence upon the swirling whirlpool of emotion, ecstasy and chaos represented by the Dionysian, is a staple across legends emerging from the ancient world. Similar to Apollo’s conquest of the Python–a symbol of man’s mastery over the chaos of Mother Nature), the Hindu Indra defeats Vritra, a demonic beast half-snake half-man, and belonging to the asuras, a class of anti-gods similar to the Greek Titans. Coming from the Proto Indo-Aryan verb -wer, meaning “to block,” or “to obstruct,” (6) Vritra prevented the flow of the sacred rivers of the Rigveda, which were then freed by Indra, bringing forth renewal, rebirth, and prosperity. Analogous myths can be found in the Babylonian Enuma Elish in the story of Marduk and Tiamat, the latter of whom is defeated by the divine king Marduk, who establishes light over darkness and order over chaos. Clear echoes are evident in the Avestan tradition, in which the Zoroastrian god-figure Ahura Mazda engages in a manichean struggle of good vs. evil against Ahriman. Odin’s restraining of Jörmungandr, the “World-Serpent,” and Tyr’s binding of the devouring wolf-beast Fenris, represent similar analogies in the Norse tradition. Finally, the appearance of the primordial Leviathan in the Old Testament attests to the firm establishment of Yahweh as the stern father-figure bringing just retribution to chaos:

"In that day the Lord with his hard and great and strong sword

will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent,

Leviathan the twisting serpent,

and he will slay the dragon that is in the sea."

— Isaiah 27:1 (ESV)

The Binding of Fenris-Carl Emil Doepler (c.1900). The god Tyr sacrifices his hand to the jaws of the mightly Fenris, destined to slay Odin, the king of the gods, during Ragnarök, the end of days. The fearsome beast is bound by the magical rope, Gleipnir.

The story arc of Western civilization follows what has been referred to as the “Faustian soul,”--that desire to transcend and overcome human adversity through attaining mastery over nature (7)-- and has largely been enshrined and encapsulated in the various myths of a hero taking on the demonic forces of chthonic darkness. One may think immediately of Odysseus, whose valiant combination of bravery, cunning, and charisma enabled his crew to survive decades lost at sea. The escape from the land of the Lotus-Eaters, where Odysseus’ crew finds itself lulled into apathy and unconsciousness from the sweat-nectar of a flower, reflects the need for man to transcend worldly pleasures and listlessness to set out into the world courageously and with singular focus. The intoxicating allure of the chthonic feminine is again seen with the seductive nymph Circe, whose mastery of potions and magic turns men into animals, and whom Odysseus must once again rescue. He does so through the instruction of the God Hermes, whereupon, drawing his sword, he forces the alluring goddess to submit, thereafter becoming her lover. Greek society at the time of Homer was a markedly masculine affair, a world where Apollonian reason and mathematical rationality gradually displaced the various mother-and-earth cults that prevailed in Hellas. Recall Apollo the god of light and reason subduing the great earth serpent. The demonic feminine, vividly depicted in the haunting magnetism of the Sirens, from whom Odysseus was forced to lash his crew to the masts lest they cast themselves overboard into a watery embrace, was perceived as a constant danger.

Ulysses and the Sirens by Herbert James Draper (1909)

In Sexual Personae, Camile Paglia takes on a largely Promethean view of the ascendance of Hellenic culture, proclaiming that “Athens became great because and not despite its misogyny.” In the Ancient Greece of Homer, women could neither own land, vote, attend the theatre or partake in philosophical discussions among the stoa (8). Much of the reason for Athenian success, Paglia argues, is that men were able to tear themselves away from the mother-cult, and in a few short years of exuberance, defiance, and self-assurance, forge a culture based on reason, logic, and precision. The downside, however, was a repression of the feminine, resulting in an emotional and psychic imbalance in society. As Amaury de Riancourt describes, since women increasingly felt it necessary to compete with men on men’s terms rather than be honoured for their god-given role as mothers, what occurred was a full revolt against motherhood and childrearing in general, the result of which was a collapse in the birthrate.(9) And, despite the efforts of various emperors–Aurelius, Valentinian, Constantine–to increase it with incentives and even a bachelor’s tax–the late Roman Empire suffered from what was called a penura homenum, a “catastrophic shortage of manpower.” (10). The most important law, the lex Iulia de pudicitia et de coercendis adulteriis (“Julian law of chastity and repression of adultery”) promulgated in 18 B.c., was the first attempt to corral sexual morality under the purview of the State. Regardless, Roman writers at the time complained about the overall wantonness and lasciviousness of Roman women, stirring Cato to complain that “all other men rule over women; but we Romans, who rule all men, are ruled by our women.” (11). In describing the attitudes and behaviour of women in pagan Rome, the early Church Father Jerome explained that some “women put on men’s clothing, cut their hair short . . . blush to be women, and prefer to look like eunuchs” (12).

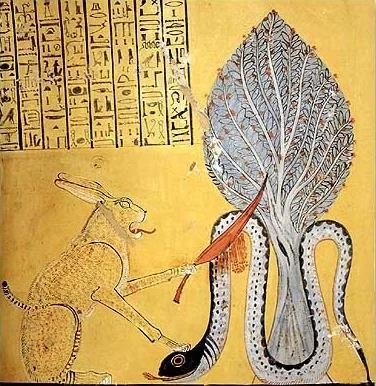

The sun god Ra slays Apep (Apophis)—the snake of chaos—as a cat (Thebes. Tomb of Inher-Kha. Reign of Ramses IV c.1164-1157)

Paglia contrasts this stark imbalance with the society of Ancient Egypt, which to a far greater extent was able to balance the Apollonian and Dionysian. The ancient land of Kemet–the “black land” in the Egyptian language–was subject to the capricious nature of the Nile, whose annual floods fertilized the land and ensured prosperity while also posing a danger to nearby settlement. Yet, despite emerging from the primordial ooze of the Nile muck, Egypt became a civilization of light and shadow, of the ascendant, triumphant erection of great temples, obelisks, and pyramids despite the undulating and mutable terrain underneath. For Paglia, the Western aesthetic, based on the straight line, sleekness, and contour, was born in Egypt and was born of the ascendance of the visual. The eye of Horus itself serves as an important symbol of the visual, that which chooses, differentiates, measures, and apprehends reality. The God Horus had first lost his eye in battle with Seth–the lord of chaos–who had murdered and dismembered his father Osiris, Lord of the underworld. Through the healing power of the scribe god Thoth, Horus reclaims his eye and is able to defeat Seth, resulting in the reestablishment of order and the resurrection of the father. Yet, despite the growing ascendance of the solar cult of Ra as Egypt entered the New Kingdom era, fertility cults such as that of Isis remained popular, and women enjoyed considerably higher legal standing, including the right to own property, swear oaths in court, access to key positions of responsibility, and symbolically powerful roles as priestesses of Hathor, Isis, and so on (13). In contrast with Greco-Roman militancy, Apollonian order, and practicality–most clearly displayed in the Hellenic deification of the horse, a stalwart, athletic and serviceable beast of burden–the Egyptians deified the cat. A slinky, mysterious, and somewhat indolent creature, the cat luxuriates and poses while engaging in sacrifices and rites of ritual purity, fastidiously cleaning itself. The cat embraces sleekness and contour, and its ritual sacredness whether in the cult of the cat goddess Bastet or its honoured role in Egyptian mythology (the slaying of the chaos serpent Apep by the solar deity Ra in the form of the cat) provides an exalted and sacralized space for the telluric feminine in union with the ascendent masculine. According to Paglia, the Egyptians invented the feminine aesthetic, by merging the sleek line of Apollonian angle with the amorphousness and voluptuousness of the Dionysian, the Egyptians were able, in effect, to pull woman out of nature and to integrate the feminine into the symbolic and mythological structure governing society. This merger is evident in the anthropomorphic hybrid-gods of ancient Egypt; sleek visages of hawk and jackal-headed deities and the deification of cats and crocodiles, beasts that move between earth and sky, water and land, contrasts with the stern purity of form in Greco-Roman statuary and evinces this balanced hybridity. Sleek Apolonian form molds the feminine as evident in the delicate contours of the famous bust of Nereftiti in a stark victory of the aesthetic.

Picture of the Nefertiti bust (Neues Museum, Berlin). Apollonian form, angle, and contour give defined shape to feminine beauty.

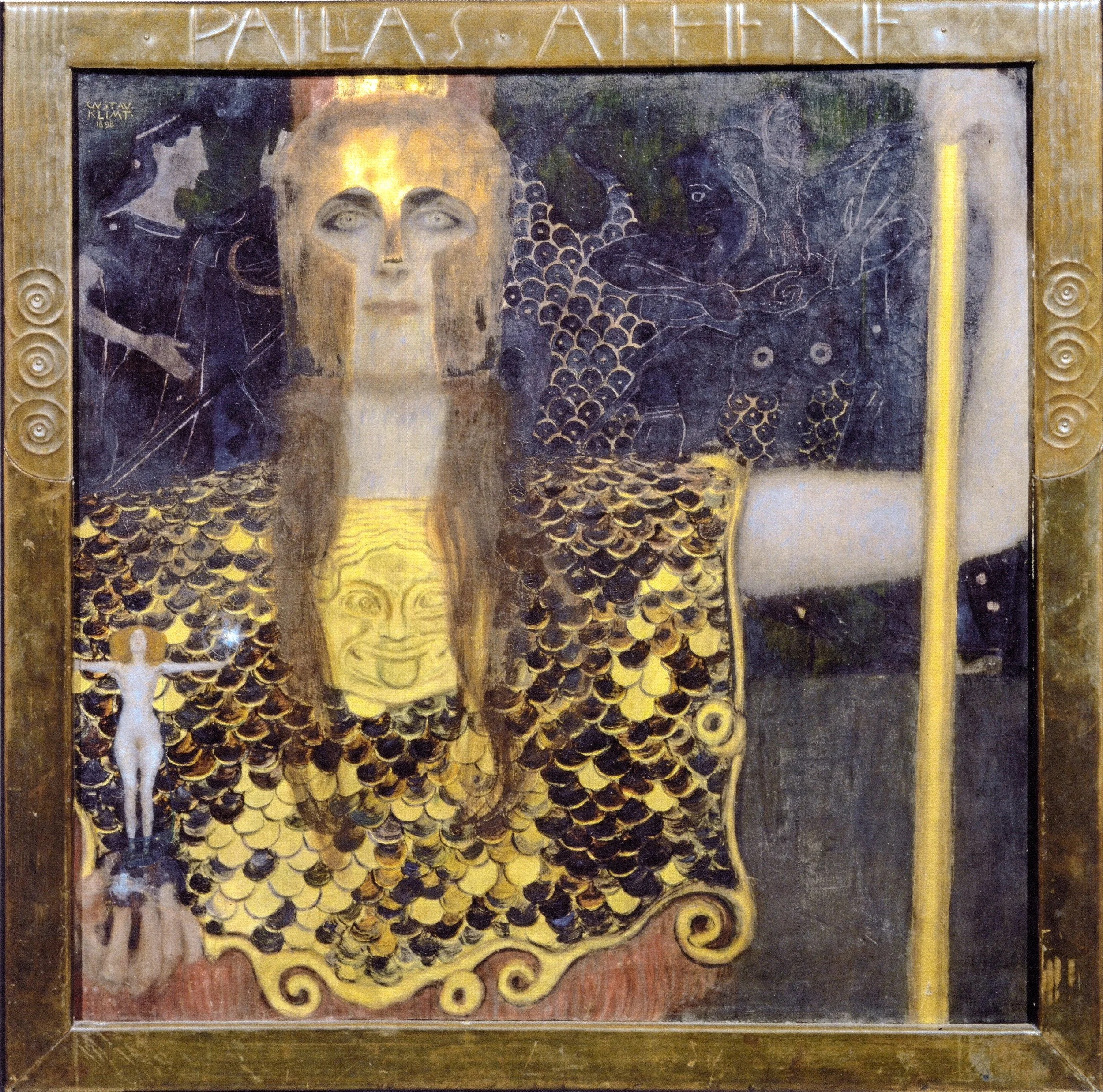

The dominance of the Apollonian over the Dionysian was solidified during the ascension of Greco-Roman civilization. The birth of the mythological Athena from the head of Zeus–emerging from the center of reason with the father as the generative factor of life–is a turning away from the mother-cult and towards a detached, resolute focus towards rationality. Athena’s militant chastity is a victory of the ascendant Apollonian principle over the chthonic and her key traits, including courage and leadership, help guide the hero Odysseus amid the lures and snares he encounters on the sea and in the underworld. Athena’s famous breastplate, the Gorgoneion, had been gifted to her by Perseus after the latter slayed the snake-haired Medusa, a powerful symbol of the vengeful, irrational, and all-devouring feminine. The Gorgoneion acted as an aegis, meant to confer protection upon friends and to curse one’s enemies, and served as a protective glyph similar to the use of the eye and hand of Fatima in the Mediterranean region today. During Homer’s time, the role of the woman was still largely honoured, especially as the matriarch and keeper of the home. One may think of Odysseus’ loyalty to his wife Penelope, whose striving to keep at bay aggressive suitors cemented her as a symbol of the devout feminine. Regardless, it was the depredations of the Trojan war and the role of Helen–whose beauty launched a thousand ships–that resulted in the fall of Troy and the disappearance of Odysseus and his crew for the subsequent twenty years. Increasingly, the feminine began to be despised as male order, discipline, and hierarchy displayed feminine intuition and emotion. Hesiod’s description of Pandora’s morbid curiosity and lack of responsibility highlights a general attitude towards woman as a punishment for the Promethean spirit of man:

For of old the tribes of men lived on the earth apart from evil and grievous toil and sore diseases that bring the fates of death to men. For in the day of evil men speedily wax old. But the woman took off the great lid of the Jar with her hands and made a scattering thereof and devised baleful sorrows for men. (14) (From Hesiod’s Works and Days)

Pallas Athene by Gustav Klimt (1898). An excellent example of Viennese Secessionism, the Gorgoneion (face of the medusa) is visibly displayed on the gold breastplate.

Women increasingly became a symbol of the indolent and luxurious Orient. The loss of Marc Antony to Cleopatra’s seductive wiles is emblematic, as the dominant archetype of Rome became the all-conquering hero Caesar. Antony’s defeat at Actium by the forces of Augustus entrenched the Pax Romana–the Roman peace–under the aegis of Apollo, Lord of the Sun. From the Rape of the Sabines onwards–when Romulus, founder of Rome ordered the abduction of women to boost the Roman population–woman’s subordinate role to man became ingrained. The chthonic mystery cults such as that of Cybele were pushed deeper underground, and would find eventual expression with the rise of Christianity. The Christian focus on compassion, charity, and its anti-aristocratic and egalitarian ethos appealed deeply to women and slaves while the role of the Virgin Mary worked to balance out the Apollonian dominance of a father god. Paglia illustrates this revolt against Apollonian dominance in classical Greece by contrasting Aeschylus’ Oresteia (458 BC) with Euripides’ Bacchae (407 BC), the former written following the outstanding victory of Athens against the Persians while the latter was written–a mere two generations later– amid the failures of the Sicilian expedition, the defeat by Sparta, and the Athenian plague (15). Aeschylus portrays the slaying of the patricidal Clytemnestra–who murdered her husband Agamemnon after his victorious return from Troy–by her son, Orestes, as the restoration of order and divine justice. During the subsequent trial, the deciding-ballot favoring Orestes is cast by none other than Athena, the goddess of war, reason and wisdom. The vengeful Furies, who were sent to swarm and haunt Orestes following his slaying of his mother, are transformed into the benevolent eumenides, or “kindly ones.” In contrast to the reasoned and measured role of the gods in the Oresteia, Euripides’ Bacchae depicts the full chaos of Dionysian excess as the god of wine arrives in Thebes and demands to be worshiped. The King Pentheus refuses to do so, choosing to oppress the Dionysian cult. He is later killed by his mother Agave, who mistakes him for a wild animal and tears him limb-from-limb, echoing the dismembering and rebirth of the Egyptian Osiris as well as the consumption of Christ’s body and blood in the Catholic rite. This violent principle of the Dionysian cult is sparagmos, a “rending,” or “tearing,” where the body of the god is torn to pieces and scattered like seed to be reborn again (16). In the tale, civilization collapses back into chaos, and disorder reigns, highlighting the alienation and confused emotions of the Athenians during this regrettable part of Greek history.

Orestes Pursued by the Furies by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1862)

The Apollonian and Dionysian form a central part of world mythology, and the delicate dance between its respective energies and drives is ignored at our peril. As the French historian Amaury de Riancourt has pointed out:

Mankind simply cannot live without myths, and this applies in our contemporary world as well, no more than he can sleep without dreaming. Myths are an inevitable concession to the anima, repressed as never before in Greece, and now again in our Western civilization. (17)

Greco-Roman culture–in contrast to the Egyptians–ignored and suppressed the Dionysian, the emotional and affective as represented by the Jungian anima, or “inner feminine.” This intuitive and spiritual side of holistic understanding later emerged through the cult of the Virgin Mary in the Catholic tradition as well as in certain Sufi currents in Islamic thought influenced by Neo-Platonism. Ibn Al-Arabi’s concept of wahdat al-wujud, or “unity of being,” is instructive as to how an inner, esoteric tradition accessible to initiatives balances out the outer, exoteric tradition represented by official and legal interpretations of key religious texts. Christian thought has also struggled–yet often succeeded–in balancing the Apollonian and Dionysian, with the logical, formulaic legalism of Thomas Aquinas and the Summa Theologiae softened with the Neo-Platonism of Augustine and notions of spiritual ascent and inner light as seen in his Confessions and City of God. While some civilizations have lurched one way or the other–ancient Byzantium’s beautiful iconography and feminine embrace of the visual subsumed by later Islamic iconoclasm and focus on the divine word–few societies have so wholly embraced Apollonian rationalism as has the West. Carl Jung, the Swiss psychologist, famously quoted that “until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” What the Western world has done, according to Jung, is exorcise the old gods:

“It is a futile undertaking to disinfect Olympus with rational enlightenment. The gods are not there: they are ensconced in the shadows of the unconscious, where we cannot uproot them.”-Carl Jung (18)

The Flapper by Frank Xavier Leyendecker (1922). An artistic rendition of the German Neue Frau, or “new woman” during the Weimar period.

This Entzauberung der Welt, or “disenchantment of the world,” in the words of German sociologist Max Weber, and, the concomitant ascent of Enlightenment rationalism at the expense of the subconscious and spiritual, has resulted in a decidedly masculinized world valuing action, drive, and productivity over being and intuitive knowing. And while this Faustian drive (to use the term of Ricardo Duchesne) has resulted in man’s ascent to the moon, it has also resulted in a world where women feel forced to succeed on men’s terms, often leading to a revolt against their own femininity. The collapse of general morality and disillusionment with traditional leadership and wisdom during the Weimar Republic following Germany’s loss in 1918, reflects the chaos of Euripides’ Bacchae, following the great plague of Athens and military defeat by Sparta. The German Neue Frau, or “new woman,” sexually liberated with short-cropped hair as well as the general fad of drag and transsexualism taking place at that time, echoes Cato’s admonitions of Rome’s loose women and lack of sexual morals. Modern-day fears of a Trumpian-style correction to Dionysian chaos–the values of the 1960s hippie and free-love generation–with Apollonian law-and-order further highlight the core imbalance between the masculine and the feminine in the modern West. To help us conclude, it would be good to quote Werner Jaeger, author of Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture:

“Mythical thought without the formative logos is blind, and logical theorizing without living mythical thought is empty.”-Werner Jaeger (19)

Until we in the West can begin to think constructively and integrally about mythology, and especially, the complementary roles of the masculine and feminine, we may remained doomed to repeat unconscious cycles, as we have seen already repeat in the ancient and more recent past.

SOURCES:

(1) Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. Translated by Douglas Smith, Oxford University Press, 2000. p.18

(2) Evola, Julius. Revolt Against the Modern World: Politics, Religion, and Social Order in the Kali Yuga. Translated by Guido Stucco, Inner Traditions International, 1995. p.

(3) Riencourt, Amaury de. Sex and Society in History. Dell Publishing Co., 1974. p.66

(4) ibid. p.133

(5) Evola. p.83

(7) Duchesne, Ricardo. Faustian Man in a Multicultural Age. Black House Publishing, 2017.

(8) Paglia, Camille. Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson. Yale University Press, 1990. p.74

(9) Riencourt. p.123

(10) ibid. p.127

(11) ibid. p.122

(12) Ibid. p.124

(13) Paglia.

(14) Riencourt. p.96

(15) Paglia. p.74-75

(16) ibid. p.71

(17) Riencourt. p.106

(18) ibid. p.107

(19) ibid. p.106

IMAGES:

(1) Shakta Ardhanari - Ardhanarishvara - Wikipedia

(3) Khalili Collection Islamic Art mss 640.1 - Gulshan-i 'Ishq - Wikipedia

(4) Emil Doepler's Die Götterwelt der Germanen Illustrations

(5) Draper_Herbert_James_Ulysses_and_the_Sirens.jpg (1589×1311)

(7) Nofretete_Neues_Museum.jpg (1282×1877)

(8) Klimt - Pallas Athene - Pallas Athena (Klimt) - Wikipedia

(9) Orestes Pursued by the Furies - Wikipedia

(10) Frank Xavier Leyendecker - The Flapper 1922 - Neue Frau (Feminismus) – Wikipedia